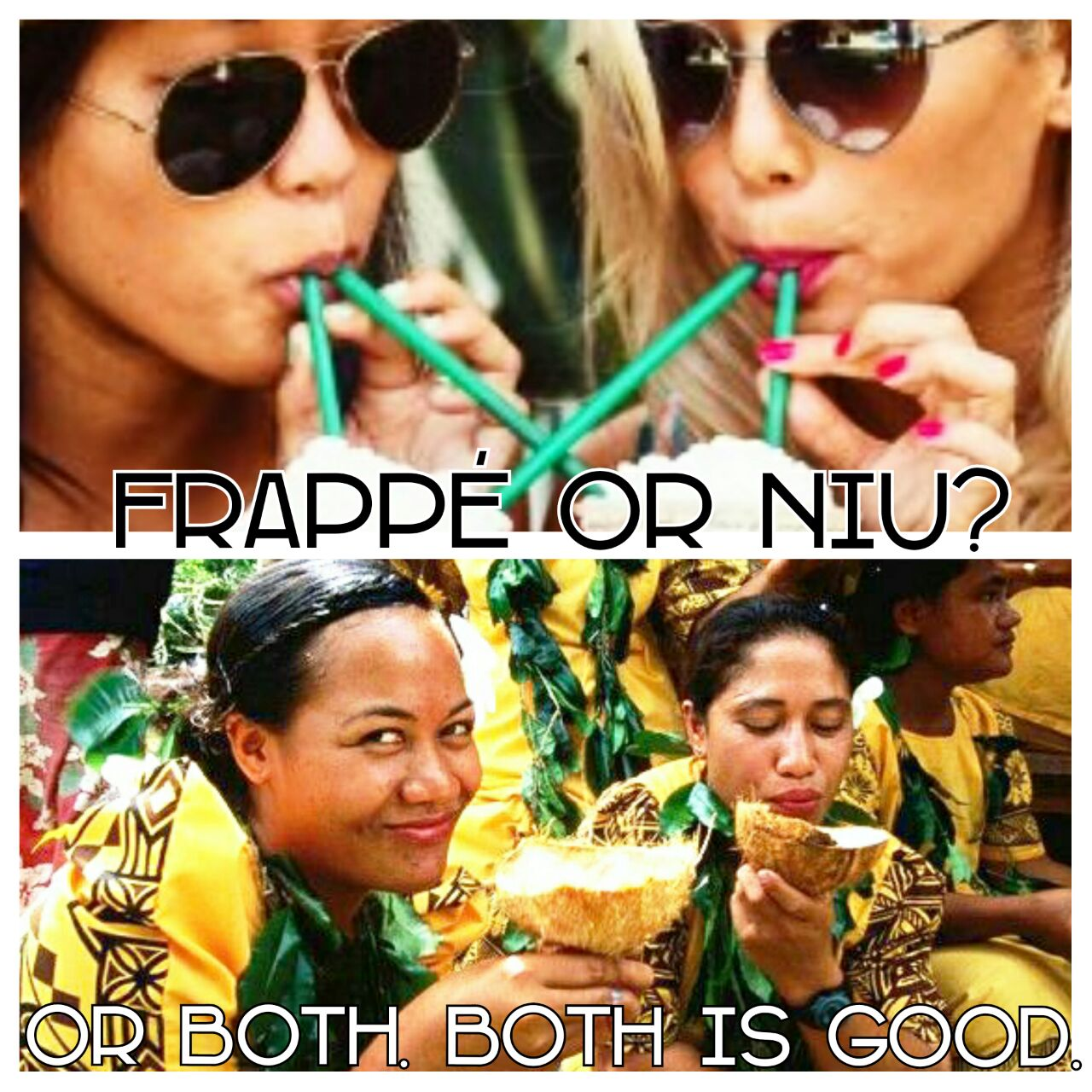

Frappé or Niu? Reconciling multicultural origins in Samoan Language Week

As we come to the end of 2015’s Samoan Language Week (O le Vaiaso o le Gagana Samoa) in New Zealand, I have to acknowledge a shadow that’s been dogging me all week.

I write for my university’s blog, an informal canvas for “our students, their voices”, so why didn’t I write about Samoan Language Week?

First and simply, we lost track of dates and didn’t realise until days before it started. Secondly, I did write something – a few things, but couldn’t publish them without a lot of thought.

It’s almost impossible to write about language without also talking about culture. And culture is one of those subjects I’m almost exhausted of discussing.

I’m tired because one constant of my life (and I imagine, for most people) is being asked, sometimes demanded, to pin down my place: draw my line in the sand and pick a side. Stand on a podium or at the foot of an altar and declare allegiance to one camp.

Well, I’ve done all of that. I’ve picked my side. I know what I stand for. I’ve said my piece, but I’ll do it again for the record.

Culture is all about how we live. Language is about how we communicate: how we speak, what we say, when and how we move, if and what we read or write. Language is a reflection of our culture. The root of words reflects the way we understand the world and our relationship with it. The word ‘life’ in Samoan is the same word for ‘water’: ‘vai’. The Samoan word for ‘Earth’ is ‘Lalolagi’, which means beneath Heaven.

One of the things I love about Samoan language is its power with proverbs. Proverbs capture the wisdom of experience learned and passed through generations – every culture has them.

There are two forms of Samoan: the formal tongue spoken at official delegations employing a lot of poetry and allegory, and the informal everyday ‘dialect’ spoken when everyone is wondering if dinner’s ready.

I am fluent in neither. I did not grow up in a Filipino or Samoan-speaking household. You’re more likely to hear me speak Samoan when I’m with children whose vocabulary is also growing. I can’t cite any Samoan proverbs without looking them up. Truthfully, my favourite Samoan phrases are things like “Ua vela le mea’ai” which means “the food is cooked” or “Malo le soifua!” translating loosely to “may your life be blessed.”

I was raised in a multicultural household. My parents come from different countries. English was the language that brought them together; faith, love and critical debate was the culture that kept them together. My parents complement each other pretty well: “Once more unto the breach!” / “But make sure you come back alive.”

I’ll never apologise for being raised in a family that loves fiercely, stood strong against doubt and criticism, and continues reconciling this intersection of communities together. We go to bed warm, fed, safe, and grateful for it. It’s a lot more than some families have.

Recently, one of my lecturers prompted me to realise how often we assess and define each other by what we lack. We’re all ‘poor’ in some way. Whether it’s poor for family, friends, money, education, or language. This is problematic because if you place the most importance on what people are lacking, the boundaries that divide us, how completely they fulfil a definition, then we ignore what that person does have. While we’re all poor for one thing or another, we’re usually rich for something else.

I don’t apologise for not knowing the Samoan language, all its rites or customs (yet) because, for me, the essence of the culture boils down to three things: love (alofa), respect (fa’aaloalo) and forgiveness (fa’amagalo).

I think Lydia Schmidt summed it up well when she said being Samoan is not about ticking criteria on a list, but holding love for the culture in your heart. How you express it will be different for every person. While we are loving and looking after one another with compassion, while we are treating each other with courtesy and respect, while we are keeping ourselves and each other accountable from harm, we’re doing all right.

But I don’t think those are uniquely Samoan qualities. And it’s fine if you don’t agree with me. People measure success in different ways, and that’s all right. But it’s important not to judge each other for it. If you’re going to call me an “afakasi fia palagi” [1] and say I’m failing to be a “keige Samoa” [2] I’ll have to point to those three tenets above and ask you where ‘prescriptive and judgmental’ truly fit in a modern fa’aSamoa.

Samoan language, culture and tradition don’t exist in a bubble frozen in time or by just one definition: we are living, thriving and growing. Investing in our language means bringing the best of the past into new and exciting directions of our future legacy. So, thank you to the speakers who continue encouraging us, who share their knowledge and love of the culture with those of us who want to learn. I hope I can do the same for others one day.

My language and culture are Samoan… and Filipino, Australian and Canadian. My camp is the world. My people are the human race. We’re more than what we each say we are, we’re more than any one label and what it means to be Samoan will continue evolving with our language and culture, because change is the only constant.

Fa’afetai lava mo le fa’aaloalo ma malo fo’i le onosa’i.

[1] Afakasi (afatasi) fia palagi: Half-caste who wants to be Caucasian

[2] Keige (teine) Samoa: Samoan girl